Making Jobs Better

A case study in improving an operator's work

In April's e-letter, I wrote about the ongoing Great Resignation and hypothesized that workers are quitting not just because of bad wages but bad jobs. Research from MIT Sloan Management Review backs up the idea indicating that a "toxic work culture" is by far the best predictor of workplace attrition. Moreover, the authors cited "disrespect” as the leading factor in a toxic work culture.

A “good job” means more than better wages and working conditions. It means demonstrating respect to workers. Lean thinking postulates that developing workers through problem-solving is fundamental to respect. By granting workers authority to solve problems management demonstrates trust by engaging workers’ minds rather than just their hands. Moreover, they enable workers to eliminate physical and mental burdens. Finally, successful development presents career opportunities beyond the assembly line or retail counter.

Management must create an environment where problems are visible, safe to discuss, and possible to solve.

Abcam is a company that has started to take this approach. It’s a rapidly growing biotechnology company headquartered in the United Kingdom with operations around the globe. Abcam entered a co-learning partnership with the Lean Enterprise Institute in the Fall of 2021 to improve its operations.

Recently, the facility in Waltham, Massachusetts tackled problems in logistics. The continuous improvement coordinator, material handler, and LEI coach teamed up to address the following problems:

- dependency on a single operator to perform material handling

- poor productivity

- stock-outs in assembly

- physical and mental burden on the material handler

Before diving into the improvements, let's look at the operation's basic steps and prior condition.

The material handler's job consisted of:

- counting supplies at four assembly areas

- retrieving supplies from the warehouse

- replenishing supplies at the four assembly areas using a dolly

At each assembly area, the material handler manually counted and wrote down the amount and type of material he had to replenish. With no clear locations for items, he frequently searched for the parts to count. And with no fixed inventory levels, it was easy to make a mistake, determining that it had enough material when it didn't.

Stock outs in assembly triggered workers to search through the warehouse. Because the assembly workers were not familiar with it, they often opened and moved boxes leading to disorganization. It was a doom-wheel effect: poor inventory management created worse inventory management.

This environment left the material handler as the sole person capable of managing inventory. Consequently, he had to keep his phone and laptop nearby on weekends and vacations in case management needed his tribal knowledge.

Let's take a look at examples of everyday struggles.

Searching for supplies to count

Winding stacks of material through the facility

Cleaning up spilled material after it toppled over

To address the problem the site’s continuous improvement coordinator and LEI coach partnered with the worker. They began by capturing the current condition and envisioning a target condition.

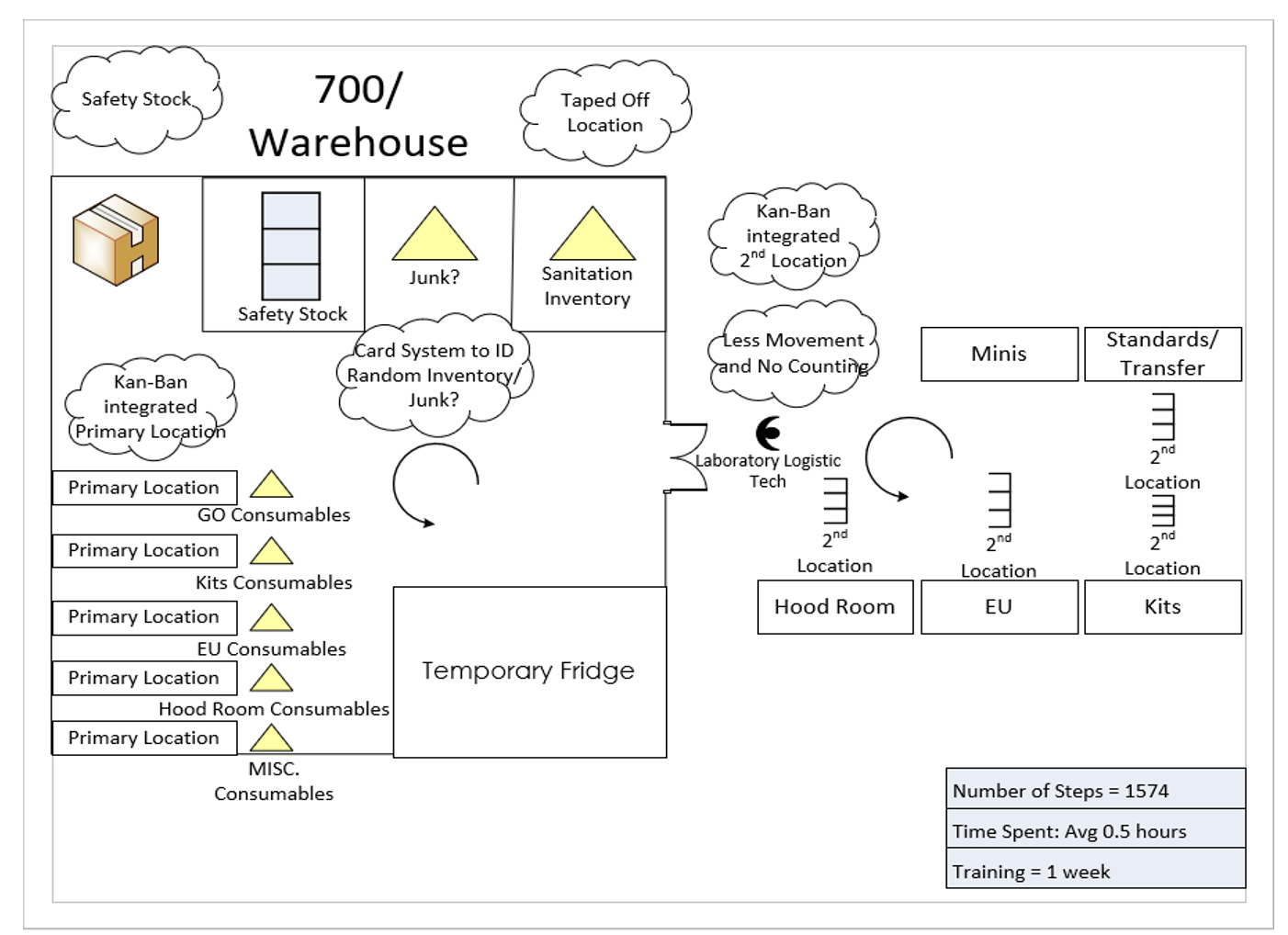

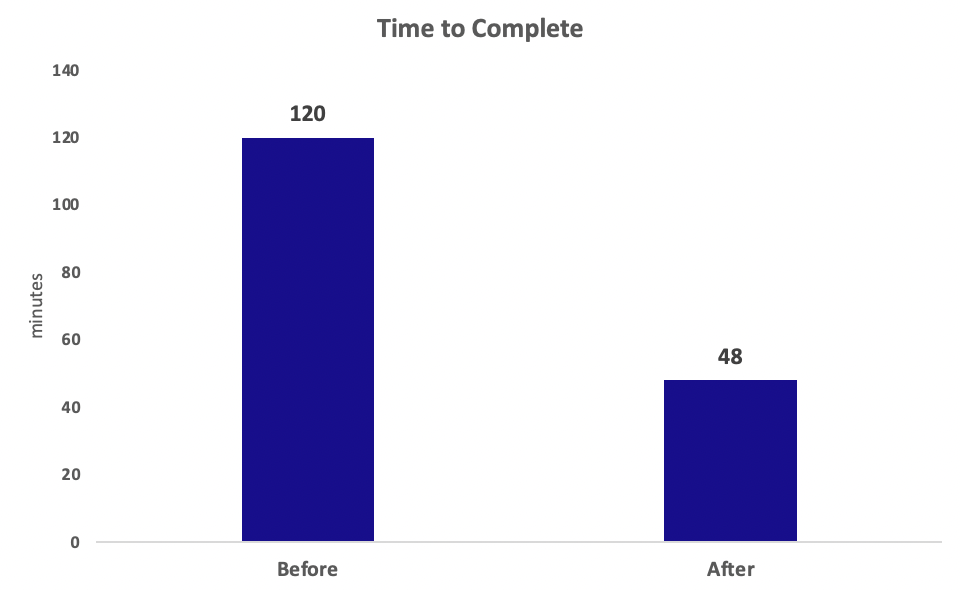

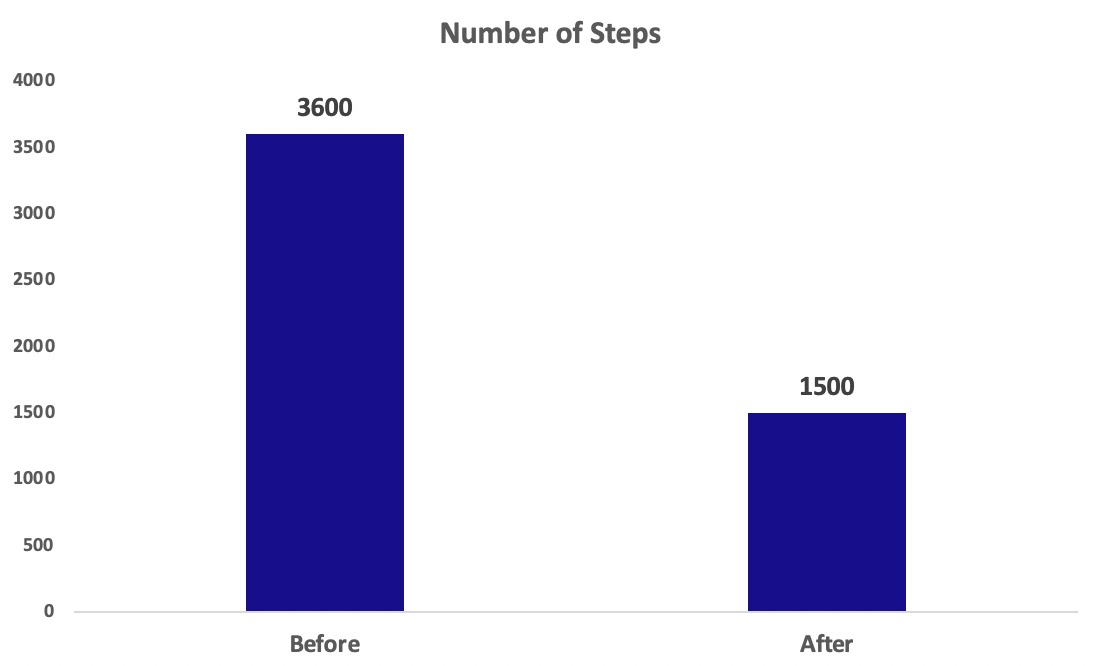

The team established clear targets to cut the number of steps in half and time required by 66%. They also laid out their plan on an A3 to build alignment.

Over three days the material handler, CI leader, and LEI coach led a team to:

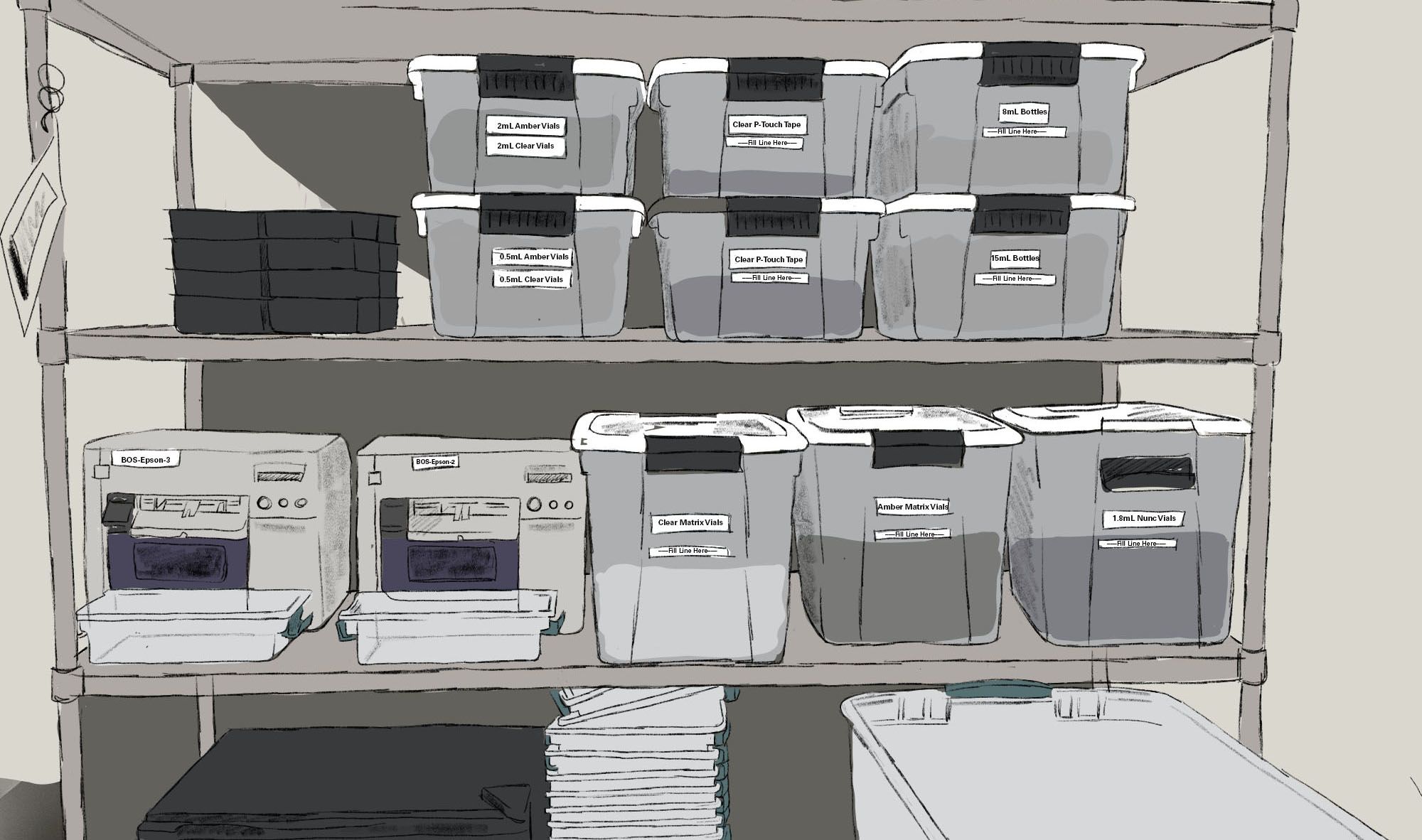

- 5S the warehouse with a clear address system for every part

- Establish 'secondary stores' at each assembly station where material permanently lived.

- Establish a two-bin replenishment system at each secondary store

Future state envisioned on the team's A3

Future state envisioned on the team's A3

Prior to taking action, the warehouse was a mess with no clear locations for materials.

The team used 5S to organize the warehouse with a clear address system.

The address system clearly guided the work from precise locations in the warehouse to precise locations in the secondary stores.

Large signs in aisles designated the high-level category of supplies stored within them. Think of a grocery store with its large, overhanding signs reading “Baking, Cereal, Chips” and “Ice Cream, Frozen Vegetables”.

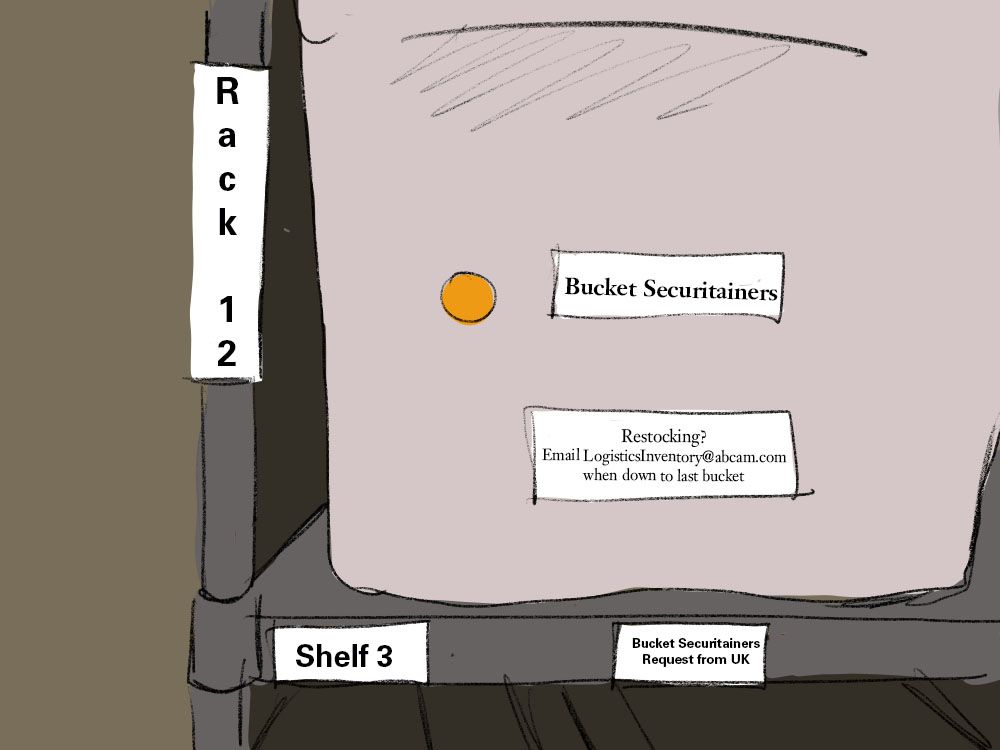

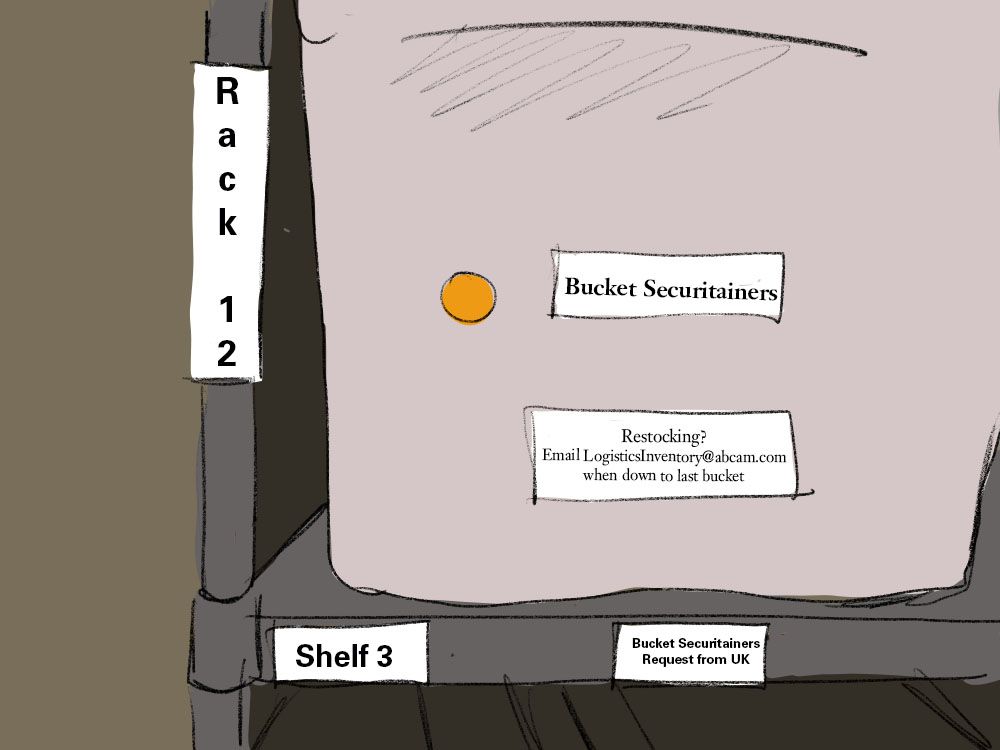

Inside the aisles, smaller signs defined the sub-category of supplies stored on each rack. Finally, simple “rack-shelf” coordinates identified the precise, fixed location of every item. For example, bucket securitainers were stored on Rack 12, Shelf 3.

Each assembly area holds a secondary store with the same “rack-shelf” system. This eliminated searching for product when counting inventory and dropping off supplies.

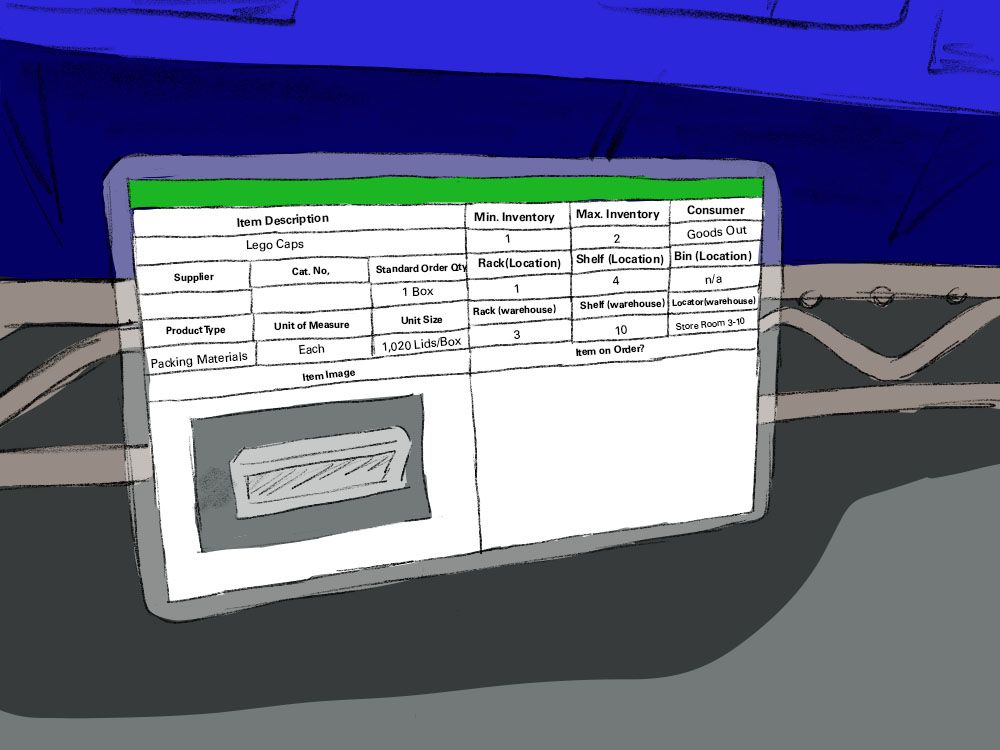

Each supply has a kanban card indicating critical information for managing its inventory, such as supplier, standard order quantity, secondary store location, and warehouse location. Now anyone can easily know how to reorder an item.

To eliminate miscounts and stockouts, the team established a two-bin replenishment system. Each item has two containers with inventory. Assembly workers pull materials from the front bin. When they pull the last item, they place the empty container on the bottom shelf. The material handler simply picks up the empty and knows to replenish it. No more miscounts. Moreover, assembly workers no longer run out of supplies because of the backup bin, which carries enough material until the resupply.

Previously, restocking happened once a day. The big batch resulted in physically demanding and slow work.

The material handler balanced a tower of supplies on a cumbersome dolly through closed doors and 90-degree turns. Boxes could easily tip over spilling supplies all over the floor.

The team decided to replenish twice per day. This allowed the material handler to use a small, more agile cart. While he's pictured with two small carts, he normally needs to handle just one allowing him to move at a comfortable speed.

All of the changes led to the team nearly achieving its targets. They cut the time required by 60% — even accounting for the second route — and the number of steps by 58%. Additionally, the material handler no longer needs to worry about weekend calls because anyone can learn this new system quickly.

Critically, the material handler co-led all of these improvements. Management gave him the authority and support to solve problems that not only made his job physically easier and mentally less stressful, but improved business performance.

The development of the worker was as important as the technical improvements. He is committed to this new, better way because he co-created it!

Let’s hear from the team on the improvement process and results.

Learn how you can make jobs easier at your organization at lean.org.